Question

Interfaces vs Types in TypeScript

What is the difference between these statements (interface vs type) in TypeScript?

interface X {

a: number

b: string

}

type X = {

a: number

b: string

};

Question

What is the difference between these statements (interface vs type) in TypeScript?

interface X {

a: number

b: string

}

type X = {

a: number

b: string

};

Solution

The current answers and the official documentation are outdated. And for those new to TypeScript, the terminology used isn't clear without examples. Below is a list of up-to-date differences.

Both can be used to describe the shape of an object or a function signature. But the syntax differs.

Interface

interface Point {

x: number;

y: number;

}

interface SetPoint {

(x: number, y: number): void;

}

Type alias

type Point = {

x: number;

y: number;

};

type SetPoint = (x: number, y: number) => void;

Unlike an interface, the type alias can also be used for other types such as primitives, unions, and tuples.

// primitive

type Name = string;

// object

type PartialPointX = { x: number; };

type PartialPointY = { y: number; };

// union

type PartialPoint = PartialPointX | PartialPointY;

// tuple

type Data = [number, string];

Both can be extended, but again, the syntax differs. Additionally, note that an interface and type alias are not mutually exclusive. An interface can extend a type alias, and vice versa.

Interface extends interface

interface PartialPointX { x: number; }

interface Point extends PartialPointX { y: number; }

Type alias extends type alias

type PartialPointX = { x: number; };

type Point = PartialPointX & { y: number; };

Interface extends type alias

type PartialPointX = { x: number; };

interface Point extends PartialPointX { y: number; }

Type alias extends interface

interface PartialPointX { x: number; }

type Point = PartialPointX & { y: number; };

A class can implement an interface or type alias, both in the same exact way. Note however that a class and interface are considered static blueprints. Therefore, they can not implement / extend a type alias that names a union type.

interface Point {

x: number;

y: number;

}

class SomePoint implements Point {

x = 1;

y = 2;

}

type Point2 = {

x: number;

y: number;

};

class SomePoint2 implements Point2 {

x = 1;

y = 2;

}

type PartialPoint = { x: number; } | { y: number; };

// FIXME: can not implement a union type

class SomePartialPoint implements PartialPoint {

x = 1;

y = 2;

}

Unlike a type alias, an interface can be defined multiple times, and will be treated as a single interface (with members of all declarations being merged).

// These two declarations become:

// interface Point { x: number; y: number; }

interface Point { x: number; }

interface Point { y: number; }

const point: Point = { x: 1, y: 2 };

Solution

Update March 2021: The newer TypeScript Handbook (also mentioned in nju-clc answer below) has a section Interfaces vs. Type Aliases which explains the differences.

Original Answer (2016)

As per the (now archived) TypeScript Language Specification:

Unlike an interface declaration, which always introduces a named object type, a type alias declaration can introduce a name for any kind of type, including primitive, union, and intersection types.

The specification goes on to mention:

Interface types have many similarities to type aliases for object type literals, but since interface types offer more capabilities they are generally preferred to type aliases. For example, the interface type

interface Point { x: number; y: number; }could be written as the type alias

type Point = { x: number; y: number; };However, doing so means the following capabilities are lost:

An interface can be named in an extends or implements clause, but a type alias for an object type literal cannotNo longer true since TS 2.7.- An interface can have multiple merged declarations, but a type alias for an object type literal cannot.

Solution

For typescript version: 4.3.4

My personal convention, which I describe below, is this:

Always prefer

interfaceovertype.

When to use type:

type when defining an alias for primitive types (string, boolean, number, bigint, symbol, etc)type when defining tuple typestype when defining function typestype when defining a uniontype when trying to overload functions in object types via compositiontype when needing to take advantage of mapped typesWhen to use interface:

interface for all object types where using type is not required (see above)interface when you want to take advantage of declaration merging.The easiest difference to see between type and interface is that only type can be used to alias a primitive:

type Nullish = null | undefined;

type Fruit = 'apple' | 'pear' | 'orange';

type Num = number | bigint;

None of these examples are possible to achieve with interfaces.

💡 When providing a type alias for a primitive value, use the type keyword.

Tuples can only be typed via the type keyword:

type row = [colOne: number, colTwo: string];

💡 Use the type keyword when providing types for tuples.

Functions can be typed by both the type and interface keywords:

// via type

type Sum = (x: number, y: number) => number;

// via interface

interface Sum {

(x: number, y: number): number;

}

Since the same effect can be achieved either way, the rule will be to use type in these scenarios since it's a little easier to read (and less verbose).

💡 Use type when defining function types.

Union types can only be achieved with the type keyword:

type Fruit = 'apple' | 'pear' | 'orange';

type Vegetable = 'broccoli' | 'carrot' | 'lettuce';

// 'apple' | 'pear' | 'orange' | 'broccoli' | 'carrot' | 'lettuce';

type HealthyFoods = Fruit | Vegetable;

💡 When defining union types, use the type keyword

An object in JavaScript is a key/value map, and an "object type" is typescript's way of typing those key/value maps. Both interface and type can be used when providing types for an object as the original question makes clear. So when do you use type vs interface for object types?

With types and composition, I can do something like this:

interface NumLogger {

log: (val: number) => void;

}

type StrAndNumLogger = NumLogger & {

log: (val: string) => void;

}

const logger: StrAndNumLogger = {

log: (val: string | number) => console.log(val)

}

logger.log(1)

logger.log('hi')

Typescript is totally happy. What about if I tried to extend that with interface:

interface StrAndNumLogger extends NumLogger {

log: (val: string) => void;

};

The declaration of StrAndNumLogger gives me an error:

Interface 'StrAndNumLogger' incorrectly extends interface 'NumLogger'

With interfaces, the subtypes have to exactly match the types declared in the super type, otherwise TS will throw an error like the one above.

💡 When trying to overload functions in object types, you'll be better off using the type keyword.

The key aspect to interfaces in typescript that distinguish them from types is that they can be extended with new functionality after they've already been declared. A common use case for this feature occurs when you want to extend the types that are exported from a node module. For example, @types/jest exports types that can be used when working with the jest library. However, jest also allows for extending the main jest type with new functions. For example, I can add a custom test like this:

jest.timedTest = async (testName, wrappedTest, timeout) =>

test(

testName,

async () => {

const start = Date.now();

await wrappedTest(mockTrack);

const end = Date.now();

console.log(`elapsed time in ms: ${end - start}`);

},

timeout

);

And then I can use it like this:

test.timedTest('this is my custom test', () => {

expect(true).toBe(true);

});

And now the time elapsed for that test will be printed to the console once the test is complete. Great! There's only one problem - typescript has no clue that i've added a timedTest function, so it'll throw an error in the editor (the code will run fine, but TS will be angry).

To resolve this, I need to tell TS that there's a new type on top of the existing types that are already available from jest. To do that, I can do this:

declare namespace jest {

interface It {

timedTest: (name: string, fn: (mockTrack: Mock) => any, timeout?: number) => void;

}

}

Because of how interfaces work, this type declaration will be merged with the type declarations exported from @types/jest. So I didn't just re-declare jest.It; I extended jest.It with a new function so that TS is now aware of my custom test function.

This type of thing is not possible with the type keyword. If @types/jest had declared their types with the type keyword, I wouldn't have been able to extend those types with my own custom types, and therefore there would have been no good way to make TS happy about my new function. This process that is unique to the interface keyword is called declaration merging.

Declaration merging is also possible to do locally like this:

interface Person {

name: string;

}

interface Person {

age: number;

}

// no error

const person: Person = {

name: 'Mark',

age: 25

};

If I did the exact same thing above with the type keyword, I would have gotten an error since types cannot be re-declared/merged. In the real world, JavaScript objects are much like this interface example; they can be dynamically updated with new fields at runtime.

💡 Because interface declarations can be merged, interfaces more accurately represent the dynamic nature of JavaScript objects than types do, and they should be preferred for that reason.

With the type keyword, I can take advantage of mapped types like this:

type Fruit = 'apple' | 'orange' | 'banana';

type FruitCount = {

[key in Fruit]: number;

}

const fruits: FruitCount = {

apple: 2,

orange: 3,

banana: 4

};

This cannot be done with interfaces:

type Fruit = 'apple' | 'orange' | 'banana';

// ERROR:

interface FruitCount {

[key in Fruit]: number;

}

💡 When needing to take advantage of mapped types, use the type keyword

Much of the time, a simple type alias to an object type acts very similarly to an interface.

interface Foo { prop: string }

type Bar = { prop: string };

However, and as soon as you need to compose two or more types, you have the option of extending those types with an interface, or intersecting them in a type alias, and that's when the differences start to matter.

Interfaces create a single flat object type that detects property conflicts, which are usually important to resolve! Intersections on the other hand just recursively merge properties, and in some cases produce never. Interfaces also display consistently better, whereas type aliases to intersections can't be displayed in part of other intersections. Type relationships between interfaces are also cached, as opposed to intersection types as a whole. A final noteworthy difference is that when checking against a target intersection type, every constituent is checked before checking against the "effective"/"flattened" type.

For this reason, extending types with interfaces/extends is suggested over creating intersection types.

Also, from the TypeScript documentation

That said, we recommend you use interfaces over type aliases. Specifically, because you will get better error messages. If you hover over the following errors, you can see how TypeScript can provide terser and more focused messages when working with interfaces like Chicken.

More in the typescript wiki.

Solution

As of TypeScript 3.2 (Nov 2018), the following is true:

| Aspect | Type | Interface |

|---|---|---|

| Can describe functions | ✅ | ✅ |

| Can describe constructors | ✅ | ✅ |

| Can describe tuples | ✅ | ✅ |

| Interfaces can extend it | ⚠️ | ✅ |

| Classes can extend it | 🚫 | ✅ |

Classes can implement it (implements) |

⚠️ | ✅ |

| Can intersect another one of its kind | ✅ | ⚠️ |

| Can create a union with another one of its kind | ✅ | 🚫 |

| Can be used to create mapped types | ✅ | 🚫 |

| Can be mapped over with mapped types | ✅ | ✅ |

| Expands in error messages and logs | ✅ | 🚫 |

| Can be augmented | 🚫 | ✅ |

| Can be recursive | ⚠️ | ✅ |

⚠️ In some cases

Solution

type?Generic Transformations

Use the type when you are transforming multiple types into a single generic type.

Example:

type Nullable<T> = T | null | undefined

type NonNull<T> = T extends (null | undefined) ? never : T

Type Aliasing

We can use the type for creating the aliases for long or complicated types that are hard to read as well as inconvenient to type again and again.

Example:

type Primitive = number | string | boolean | null | undefined

Creating an alias like this makes the code more concise and readable.

Type Capturing

Use the type to capture the type of an object when the type is unknown.

Example:

const orange = { color: "Orange", vitamin: "C"}

type Fruit = typeof orange

let apple: Fruit

Here, we get the unknown type of orange, call it a Fruit and then use the Fruit to create a new type-safe object apple.

interface?Polymorphism

An interface is a contract to implement a shape of the data. Use the interface to make it clear that it is intended to be implemented and used as a contract about how the object will be used.

Example:

interface Bird {

size: number

fly(): void

sleep(): void

}

class Hummingbird implements Bird { ... }

class Bellbird implements Bird { ... }

Though you can use the type to achieve this, the Typescript is seen more as an object oriented language and the interface has a special place in object oriented languages. It's easier to read the code with interface when you are working in a team environment or contributing to the open source community. It's easy on the new programmers coming from the other object oriented languages too.

The official Typescript documentation also says:

... we recommend using an

interfaceover atypealias when possible.

This also suggests that the type is more intended for creating type aliases than creating the types themselves.

Declaration Merging

You can use the declaration merging feature of the interface for adding new properties and methods to an already declared interface. This is useful for the ambient type declarations of third party libraries. When some declarations are missing for a third party library, you can declare the interface again with the same name and add new properties and methods.

Example:

We can extend the above Bird interface to include new declarations.

interface Bird {

color: string

eat(): void

}

That's it! It's easier to remember when to use what than getting lost in subtle differences between the two.

Solution

TypeScript handbook gives the answer:

Almost all features of an interface are available in type.

The key distinction is that a type cannot be re-opened to add new properties vs an interface which is always extendable.

Solution

https://www.typescriptlang.org/docs/handbook/2/types-from-types.html (Go to the new page)

https://www.typescriptlang.org/docs/handbook/advanced-types.html (This page has been deprecated)

One difference is that interfaces create a new name that is used everywhere. Type aliases don’t create a new name — for instance, error messages won’t use the alias name.

Solution

// create a tree structure for an object. You can't do the same with interface because of lack of intersection (&)

type Tree<T> = T & { parent: Tree<T> };

// type to restrict a variable to assign only a few values. Interfaces don't have union (|)

type Choise = "A" | "B" | "C";

// thanks to types, you can declare NonNullable type thanks to a conditional mechanism.

type NonNullable<T> = T extends null | undefined ? never : T;

// you can use interface for OOP and use 'implements' to define object/class skeleton

interface IUser {

user: string;

password: string;

login: (user: string, password: string) => boolean;

}

class User implements IUser {

user = "user1"

password = "password1"

login(user: string, password: string) {

return (user == user && password == password)

}

}

// you can extend interfaces with other interfaces

interface IMyObject {

label: string,

}

interface IMyObjectWithSize extends IMyObject{

size?: number

}

Solution

Other answers are great! Few other things which Type can do but Interface can't

type Name = string | { FullName: string };

const myName = "Jon"; // works fine

const myFullName: Name = {

FullName: "Jon Doe", //also works fine

};

type Keys = "firstName" | "lastName";

type Name = {

[key in Keys]: string;

};

const myName: Name = {

firstName: "jon",

lastName: "doe",

};

extends)type Name = {

firstName: string;

lastName: string;

};

type Address = {

city: string;

};

const person: Name & Address = {

firstName: "jon",

lastName: "doe",

city: "scranton",

};

Also not that type was introduced later as compared to interface and according to the latest release of TS type can do *almost everything which interface can and much more!

*except Declaration merging (personal opinion: It's good that it's not supported in type as it may lead to inconsistency in code)

Solution

Difference in indexing.

interface MyInterface {

foobar: string;

}

type MyType = {

foobar: string;

}

const exampleInterface: MyInterface = { foobar: 'hello world' };

const exampleType: MyType = { foobar: 'hello world' };

let record: Record<string, string> = {};

record = exampleType; // Compiles

record = exampleInterface; // Index signature is missing

Related issue: Index signature is missing in type (only on interfaces, not on type alias)

So please consider this example, if you want to index your object

Take a look on this question and this one about violation of Liskov principle

Difference in evaluation

See the result type of ExtendFirst when FirstLevelType is interface

/**

* When FirstLevelType is interface

*/

interface FirstLevelType<A, Z> {

_: "typeCheck";

};

type TestWrapperType<T, U> = FirstLevelType<T, U>;

const a: TestWrapperType<{ cat: string }, { dog: number }> = {

_: "typeCheck",

};

// { cat: string; }

type ExtendFirst = typeof a extends FirstLevelType<infer T, infer _>

? T

: "not extended";

See the result type of ExtendFirst when FirstLevelType is a type:

/**

* When FirstLevelType is type

*/

type FirstLevelType<A, Z>= {

_: "typeCheck";

};

type TestWrapperType<T, U> = FirstLevelType<T, U>;

const a: TestWrapperType<{ cat: string }, { dog: number }> = {

_: "typeCheck",

};

// unknown

type ExtendFirst = typeof a extends FirstLevelType<infer T, infer _>

? T

: "not extended";

Solution

The key difference pointed out in the documentation is that Interface can be reopened to add new property but Type alias cannot be reopened to add new property eg:

This is ok

interface x {

name: string

}

interface x {

age: number

}

this will throw the error Duplicate identifier y

type y = {

name: string

}

type y = {

age: number

}

Asides from that both interface and type alias are similar.

Solution

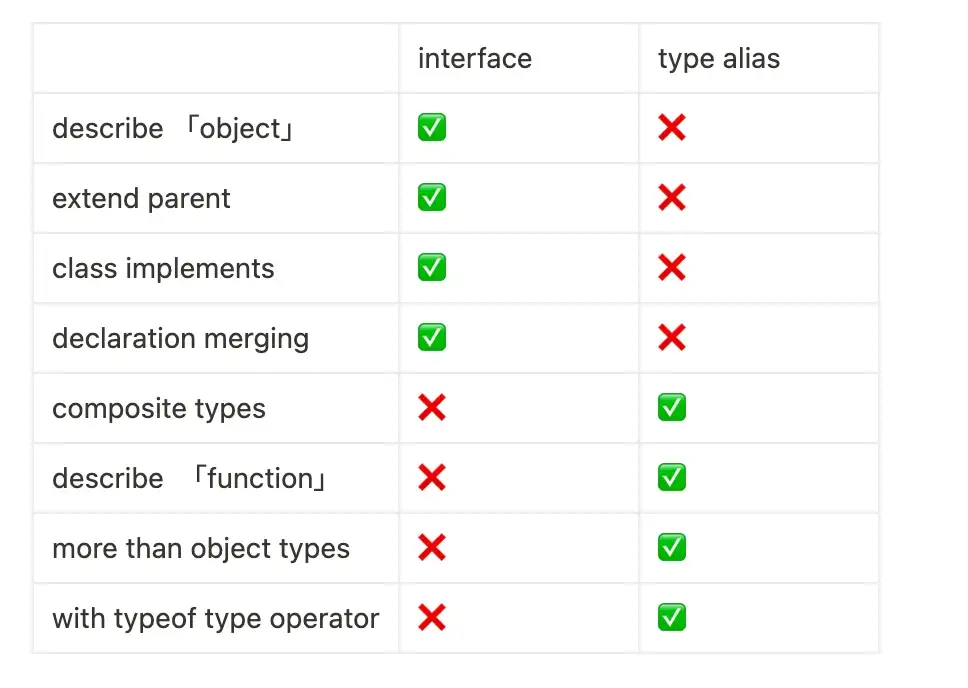

In my daily development, I use this cheatsheet when I don't know which to choose.

For more information, you can read my blog: https://medium.com/@magenta2127/use-which-interface-or-type-alias-in-typescript-bdfaf2e882ae

Solution

In typescript, "interface" is recommended over "type".

"type" is used for creating type aliases. You cannot do this with "interface".

type Data=string

Then instead of using string, you can use "Data"

const name:string="Yilmaz"

const name:Data="Yilmaz"

Aliases are very useful especially working with generic types.

Declaration Merging: You can merge interfaces but not types.

interface Person {

name: string;

}

interface Person {

age: number;

}

// we have to provide properties in both Person

const me: Person = {

name: "Yilmaz",

age: 30

};

functional programming users use "type", object-oriented programing users choose "interface"

You can’t have computed or calculated properties on interfaces but in type.

type Fullname = "firstname" | "lastname"

type Person= {

[key in Fullname]: string

}

const me: Person = {

firstname: "Yilmaz",

lastname: "Bingol"

}

Solution

In addition to the brilliant answers already provided, there are noticeable differences when it comes to extending types vs interfaces. I recently ran into a couple of cases where an interface couldn't do the job:

Solution

Interfaces and types are used to describe the types of objects and primitives. Both interfaces and types can often be used interchangeably and often provide similar functionality. Usually it is the choice of the programmer to pick their own preference.

However, interfaces can only describe objects and classes that create these objects. Therefore types must be used in order to describe primitives like strings and numbers.

Here is an example of 2 differences between interfaces and types:

// 1. Declaration merging (interface only)

// This is an extern dependency which we import an object of

interface externDependency { x: number, y: number; }

// When we import it, we might want to extend the interface, e.g. z:number

// We can use declaration merging to define the interface multiple times

// The declarations will be merged and become a single interface

interface externDependency { z: number; }

const dependency: externDependency = {x:1, y:2, z:3}

// 2. union types with primitives (type only)

type foo = {x:number}

type bar = { y: number }

type baz = string | boolean;

type foobarbaz = foo | bar | baz; // either foo, bar, or baz type

// instances of type foobarbaz can be objects (foo, bar) or primitives (baz)

const instance1: foobarbaz = {y:1}

const instance2: foobarbaz = {x:1}

const instance3: foobarbaz = true

Solution

When it comes to compilation speed, composed interfaces perform better than type intersections:

[...] interfaces create a single flat object type that detects property conflicts. This is in contrast with intersection types, where every constituent is checked before checking against the effective type. Type relationships between interfaces are also cached, as opposed to intersection types.

Source: https://github.com/microsoft/TypeScript/wiki/Performance#preferring-interfaces-over-intersections

Solution

Want to add my 2 cents;

I used to be "an interface lover" (preferring interface to type except for Unions, Intersections etc)... until I started to use the type "any key-value object" a.k.a Record<string, unknown>

If you type something as "any key-value object":

function foo(data: Record<string, unknown>): void {

for (const [key, value] of Object.entries(data)) {

// whatever

}

}

You might reach an dead end if you use interface

interface IGoo {

iam: string;

}

function getGoo(): IGoo {

return { iam: 'an interface' };

}

const goo = getGoo();

foo(goo); // ERROR

// Argument of type 'IGoo' is not assignable to parameter of type

// 'Record<string, unknown>'.

// Index signature for type 'string' is missing in type

// 'IGoo'.ts(2345)

While type just works like a charm:

type Hoo = {

iam: string;

};

function getHoo(): Hoo {

return { iam: 'a type' };

}

const hoo = getHoo();

foo(hoo); // works

This particular use case - IMO - makes the difference.

Solution

Here's another difference. I will... buy you a beer if you can explain the reasoning or reason as to this state of affairs:

enum Foo { a = 'a', b = 'b' }

type TFoo = {

[k in Foo]: boolean;

}

const foo1: TFoo = { a: true, b: false} // good

// const foo2: TFoo = { a: true } // bad: missing b

// const foo3: TFoo = { a: true, b: 0} // bad: b is not a boolean

// So type does roughly what I'd expect and want

interface IFoo {

// [k in Foo]: boolean;

/*

Uncommenting the above line gives the following errors:

A computed property name in an interface must refer to an expression whose type is a

literal type or a 'unique symbol' type.

A computed property name must be of type 'string', 'number', 'symbol', or 'any'.

Cannot find name 'k'.

*/

}

// ???

This sort of makes me want to say the hell with interfaces unless I'm intentionally implementing some OOP design pattern, or require merging as described above (which I'd never do unless I had a very good reason for it).

Solution

tldr; use interfaces for "classes", use types for most other things.

types better capture the dynamic nature of most JavaScript code

For the most part, the type better support most of the constructs that you can meet in JavaScript.

As an example, I'll use fetch-mock, which can be used to test code making fetch requests. The library is quite flexible in how you can setup your expectations.

fetchMock.get("http://example.com", response);

fetchMock.get(/\/users/, response);

fetchMock.get({ url: "http://example.com", query: { q: 'foo' } }, response);

fetchMock.mock({ method: 'get', url: "..." }, response);

This list of examples is far from complete.

The union types (which don't work with interfaces) is perfect for describing this type of input.

get(matcher: string | RegExp | { method?:'get', url?: string, query?: {} })

mock(matcher: string | RegExp | { method: 'get'|'put'|'post', ...})

interfaces work well with code that is intended for monkey patching

I am currently writing a medium article about this, and in the process I read a lot of what others write (which brought me to this SO question also).

Some are really good at describing the syntax, and how declaration merging works. But I find that most fail to explain why this is not just a good idea; it is essential for TypeScript to be useful at all.

The thing is, in JavaScript, "classes" can be monkey patched, i.e. you can add new functions, or modify existing functions at runtime.

I will use chai as an example.

Chai is an assertion library for unit testing, and it allows you to write fluent assertion code like this:

test('user', () => {

const actual = getUser();

actual.should.deep.equal({

firstName: "John,

lastName: "Doe"

})

})

Chai makes this possible is by actually modifying the native JavaScript Object prototype. Since everything inherits from Object, the syntax works for all values (except null and undefined)

Object.defineProperty(Object.prototype, 'should', { ... })

The TypeScript definition of interface Object can be found in /lib/lib.es5.d.ts in the typescript npm module. It looks like this:

interface Object {

/** The initial value of Object.prototype.constructor is the standard built-in Object constructor. */

constructor: Function;

/** Returns a string representation of an object. */

toString(): string;

/** Returns a date converted to a string using the current locale. */

toLocaleString(): string;

...

}

So now, TypeScript knows that everything, which is not null or undefined will have a toString() function.

But TypeScript doesn't know about the new property from chai, so the example above would generate a TypeScript compiler error.

As this is not an uncommon JavaScript practice, TypeScript would be useless if this type of code could not be properly supported. And that's why the declaration merging of interfaces is crucial to making TypeScript useful.

Since chai itself is not written in TypeScript, the support is added by the @types/chai library, the relevant code is in index.d.ts and looks like this:

interface Object {

should: Chai.Assertion;

}

Once you have added that module, the TypeScript compiler will know that should is also a valid property on every object.

Chai itself has a plug-in architecture, that allows you to add new types of assertions. For example, sinon-chai adds assertions for spys, stubs, or mocks created with sinon

const spy = sinon.spy();

spy(42);

spy.should.have.been.calledOnceWith(42)

This is possible to describe because the Chai.Assertion from before is defined as an interface, not a type alias. And the typescript definitions for sinon-chai adds to that specific interface.

So if you have classes, they could potentially be monkey patched, you should use an interface to describe them.

If you write the class in TypeScript you actually get the interface out of the box:

class Foo {}

This creates both a value Foo and an interface Foo, and other libraries extending your code, can add to the interface Foo.

So mostly don't have to define interfaces explicitly for your TypeScript code. They can help if you want to have multiple classes conform to a common interface.

When creating or maintaining TypeScript definitions for pure JavaScript modules, interfaces should probably be used for everything that is a class in the original module; particularly examples like chai, where the modules are designed to be extended through plug-ins.

NOTE: I would just add that the interface that is created for your class automatically is an interface of the public members of the class. It tells nothing of inheritance, which can surprise people with a Java/C# background.

class Foo {

print() { console.log("foo") }

}

function printFoo(foo: Foo) {

foo.print();

}

// Valid of course,

printFoo(new Foo());

// Also valid - which might be surprising.

printFoo({ print: () => {} });

NOTE: Also, as a class in TypeScript create both a value and an interface type, you can both "extend" and "implement" the class name.

class Foo {

print()

}

// extends is a JavaScript construct. This defines an inheritance

// relationship. Here it's the _value_ Foo, that is referred to

class A extends Foo {}

// implements is a TypeScript, not JavaScript, construct. This refers

// to the _interface_ Foo.

class B implements Foo {

print() {} // Necessary to correctly implement Foo

}

Solution

Demonstrate the ability to recursively re-write Object Literal types and interfaces recursively and not class members/properties/functions.

Also how to distinguish and type check differences and workaround to the problem discussed above, when Record<any, string|number> doesn't work due being interfaces and things like that, you work around it. This would allow for simplifications to the following potentially for mongoose types: https://github.com/wesleyolis/mongooseRelationalTypes mongooseRelationalTypes, DeepPopulate, populate

Also, a bunch of another approaches to do advanced type generics and type inference and the quirks around it for speed, all little tricks to get them right from many experiments, of trial and error.

Typescript playground: Click here for all examples in a live play ground

class TestC {

constructor(public a: number, public b: string, private c: string) {

}

}

class TestD implements Record<any, any> {

constructor(public a: number, public b: string, private c: string) {

}

test() : number {

return 1;

}

}

type InterfaceA = {

a: string,

b: number,

c: Date

e: TestC,

f: TestD,

p: [number],

neastedA: {

d: string,

e: number

h: Date,

j: TestC

neastedB: {

d: string,

e: number

h: Date,

j: TestC

}

}

}

type TCheckClassResult = InterfaceA extends Record<any, unknown> ? 'Y': 'N' // Y

const d = new Date();

type TCheckClassResultClass = typeof d extends Record<any, unknown> ? 'Y': 'N' // N

const metaData = Symbol('metaData');

type MetaDataSymbol = typeof metaData;

// Allows us to not recuse into class type interfaces or traditional interfaces, in which properties and functions become optional.

type MakeErrorStructure<T extends Record<any, any>> = {

[K in keyof T] ?: (T[K] extends Record<any, unknown> ? MakeErrorStructure<T[K]>: T[K] & Record<MetaDataSymbol, 'customField'>)

}

type MakeOptional<T extends Record<any, any>> = {

[K in keyof T] ?: T[K] extends Record<any, unknown> ? MakeOptional<T[K]> : T[K]

}

type RRR = MakeOptional<InterfaceA>

const res = {} as RRR;

const num = res.e!.a; // type == number

const num2 = res.f!.test(); // type == number

Making recursive shapes or keys of specific shape recursive

type MakeRecusive<Keys extends string, T> = {

[K in Keys]: T & MakeRecusive<K, T>

} & T

type MakeRecusiveObectKeys<TKeys extends string, T> = {

[K in keyof T]: K extends TKeys ? T[K] & MakeRecusive<K, T[K]>: T[K]

}

How to apply type constraints, for Record Types, which can validate interfaces like Discriminators:

type IRecordITypes = string | symbol | number;

// Used for checking interface, because Record<'key', Value> excludeds interfaces

type IRecord<TKey extends IRecordITypes, TValue> = {

[K in TKey as `${K & string}`] : TValue

}

// relaxies the valiation, older versions can't validate.

// type IRecord<TKey extends IRecordITypes, TValue> = {

// [index: TKey] : TValue

// }

type IRecordAnyValue<T extends Record<any,any>, TValue> = {

[K in keyof T] : TValue

}

interface AA {

A : number,

B : string

}

interface BB {

A: number,

D: Date

}

// This approach can also be used, for indefinitely recursive validation like a deep populate, which can't determine what validate beforehand.

interface CheckRecConstraints<T extends IRecordAnyValue<T, number | string>> {

}

type ResA = CheckRecConstraints<AA> // valid

type ResB = CheckRecConstraints<BB> // invalid

Alternative for checking keys:

type IRecordKeyValue<T extends Record<any,any>, TKey extends IRecordITypes, TValue> =

{

[K in keyof T] : (TKey & K) extends never ? never : TValue

}

// This approach can also be used, for indefinitely recursive validation like a deep populate, which can't determine what validate beforehand.

interface CheckRecConstraints<T extends IRecordKeyValue<T, number | string, number | string>> {

A : T

}

type UUU = IRecordKeyValue<AA, string, string | number>

type ResA = CheckRecConstraints<AA> // valid

type ResB = CheckRecConstraints<BB> // invalid

Example of using Discriminators, however, for speed I would rather use literally which defines each key to Record and then have passed to generate the mixed values because use less memory and be faster than this approach.

type EventShapes<TKind extends string> = IRecord<TKind, IRecordITypes> | (IRecord<TKind, IRecordITypes> & EventShapeArgs)

type NonClassInstance = Record<any, unknown>

type CheckIfClassInstance<TCheck, TY, TN> = TCheck extends NonClassInstance ? 'N' : 'Y'

type EventEmitterConfig<TKind extends string = string, TEvents extends EventShapes<TKind> = EventShapes<TKind>, TNever = never> = {

kind: TKind

events: TEvents

noEvent: TNever

}

type UnionDiscriminatorType<TKind extends string, T extends Record<TKind, any>> = T[TKind]

type PickDiscriminatorType<TConfig extends EventEmitterConfig<any, any, any>,

TKindValue extends string,

TKind extends string = TConfig['kind'],

T extends Record<TKind, IRecordITypes> & ({} | EventShapeArgs) = TConfig['events'],

TNever = TConfig['noEvent']> =

T[TKind] extends TKindValue

? TNever

: T extends IRecord<TKind, TKindValue>

? T extends EventShapeArgs

? T['TArgs']

: [T]

: TNever

type EventEmitterDConfig = EventEmitterConfig<'kind', {kind: string | symbol}, any>

type EventEmitterDConfigKeys = EventEmitterConfig<any, any> // Overide the cached process of the keys.

interface EventEmitter<TConfig extends EventEmitterConfig<any, any, any> = EventEmitterDConfig,

TCacheEventKinds extends string = UnionDiscriminatorType<TConfig['kind'], TConfig['events']>

> {

on<TKey extends TCacheEventKinds,

T extends Array<any> = PickDiscriminatorType<TConfig, TKey>>(

event: TKey,

listener: (...args: T) => void): this;

emit<TKey extends TCacheEventKinds>(event: TKey, args: PickDiscriminatorType<TConfig, TKey>): boolean;

}

Example of usage:

interface EventA {

KindT:'KindTA'

EventA: 'EventA'

}

interface EventB {

KindT:'KindTB'

EventB: 'EventB'

}

interface EventC {

KindT:'KindTC'

EventC: 'EventC'

}

interface EventArgs {

KindT:1

TArgs: [string, number]

}

const test :EventEmitter<EventEmitterConfig<'KindT', EventA | EventB | EventC | EventArgs>>;

test.on("KindTC",(a, pre) => {

})

Better Approach to discriminate types and Pick Types from a map for narrowing, which typically results in faster performance and less overhead to type manipulation and allow improved caching. compare to the previous example above.

type IRecordKeyValue<T extends Record<any,any>, TKey extends IRecordITypes, TValue> =

{

[K in keyof T] : (TKey & K) extends never ? never : TValue

}

type IRecordKeyRecord<T extends Record<any,any>, TKey extends IRecordITypes> =

{

[K in keyof T] : (TKey & K) extends never ? never : T[K] // need to figure out the constrint here for both interface and records.

}

type EventEmitterConfig<TKey extends string | symbol | number, TValue, TMap extends IRecordKeyValue<TMap, TKey, TValue>> = {

map: TMap

}

type PickKey<T extends Record<any,any>, TKey extends any> = (T[TKey] extends Array<any> ? T[TKey] : [T[TKey]]) & Array<never>

type EventEmitterDConfig = EventEmitterConfig<string | symbol, any, any>

interface TDEventEmitter<TConfig extends EventEmitterConfig<any, any, TConfig['map']> = EventEmitterDConfig,

TMap = TConfig['map'],

TCacheEventKinds = keyof TMap

> {

on<TKey extends TCacheEventKinds, T extends Array<any> = PickKey<TMap, TKey>>(event: TKey,

listener: (...args: T) => void): this;

emit<TKey extends TCacheEventKinds, T extends Array<any> = PickKey<TMap, TKey>>(event: TKey, ...args: T): boolean;

}

type RecordToDiscriminateKindCache<TKindType extends string | symbol | number, TKindName extends TKindType, T extends IRecordKeyRecord<T, TKindType>> = {

[K in keyof T] : (T[K] & Record<TKindName, K>)

}

type DiscriminateKindFromCache<T extends IRecordKeyRecord<T, any>> = T[keyof T]

Example of usages:

interface EventA {

KindT:'KindTA'

EventA: 'EventA'

}

interface EventB {

KindT:'KindTB'

EventB: 'EventB'

}

interface EventC {

KindT:'KindTC'

EventC: 'EventC'

}

type EventArgs = [number, string]

type Items = {

KindTA : EventA,

KindTB : EventB,

KindTC : EventC

//0 : EventArgs,

}

type DiscriminatorKindTypeUnionCache = RecordToDiscriminateKindCache<string

//| number,

"KindGen", Items>;

type CachedItemForSpeed = DiscriminatorKindTypeUnionCache['KindTB']

type DiscriminatorKindTypeUnion = DiscriminateKindFromCache<DiscriminatorKindTypeUnionCache>;

function example() {

const test: DiscriminatorKindTypeUnion;

switch(test.KindGen) {

case 'KindTA':

test.EventA

break;

case 'KindTB':

test.EventB

break;

case 'KindTC':

test.EventC

case 0:

test.toLocaleString

}

}

type EmitterConfig = EventEmitterConfig<string

//| number

, any, Items>;

const EmitterInstance :TDEventEmitter<EmitterConfig>;

EmitterInstance.on("KindTB",(a, b) => {

a.

})

Solution

As for choosing one over the other, I believe it is best said in the second edition of the TypeScript Handbook:

For the most part, you can choose based on personal preference, and TypeScript will tell you if it needs something to be the other kind of declaration. If you would like a heuristic, use interface until you need to use features from type.

You can read the whole comparison between type and interface in the Handbook (part of the official TypeScript documentation).

At the time of writing this answer, the version of TypeScript is 5.1

Solution

Based on all the discussions I've seen or engaged recently the main difference between types and interfaces is that interfaces can be extended and types can't.

Also if you declare a interface twice they will be merged into a single interface. You can't do it with types.

Solution

I’d like to clarify it is not just a personal choice between interface and type when defining an object type in TS. They differ in the underlying mechanism of how TS evaluate them.

Previous answers have already pointed out the difference in semantics between interface and type, like interface can use declaration merging, while type can not. But the real difference is that interface is a real type definition, while type is just an alias of a type. When TS evaluate them, interface is lazy, it will only be expanded when necessary, while type is eager, it will be expanded immediately.

Let’s see an example:

type Boxed<T> = { value: T };

type BoxedString = Boxed<BoxedString> | string;

If you paste the above code to TS playground, you will get an error, and type of BoxedString will be any:

type BoxedString = Boxed<BoxedString> | string;

// ~~~~~~~~~~~

// Type alias 'BoxedString' circularly references itself.(2456)

Why? Doesn’t TS support recursive type definition? No, it does. It is common to define a tree-like structure in TS:

type TreeNode<T> = {

value: T;

left: TreeNode<T>;

right: TreeNode<T>;

};

You can define the TreeNode type without any problem, either using type or interface. The problem originates from the eager evaluation of type. If we replace type with interface in the above example, it will work:

interface Boxed<T> {

value: T;

}

type BoxedString = Boxed<BoxedString> | string;

Or just use an object literal type without defining a Boxed type:

type BoxedString = { value: BoxedString } | string;

Why? According to my experience, object literal types and types defined using interface are lazy, that is, they will not be expanded until they are used. Let’s try to expand the original BoxedString type manually:

type BoxedString = Boxed<BoxedString> | string;

// TS find `Boxed` is a type alias, so it will expand `Boxed<BoxedString>` immediately

// to expand it, it should first expand `BoxedString` inside `Boxed<BoxedString>`

// To expand `BoxedString`, it should first expand `Boxed<BoxedString>` immediately

// ... Never ending

However, when Boxed is defined by interface, TS will not try to expand Boxed<BoxedString> immediately, it will wait until BoxedString is used. The same thing happens when using object literal types.

So, what’s the difference between interface and type? interface is a real type definition, while type is just an alias of a type. When TS evaluate them, interface is lazy, it will only be expanded when necessary, while type is eager, it will be expanded immediately.

It is not rare to use recursive type definition in TS – especially for library authors. My advice is to always use interface when defining an object type, it also enables declaration merging, which is very useful when you’re writing a library and later someone wants to write an extension for it.

Solution

Interface was designed specifically to describe object shapes; however Types are somehow like interfaces that can be used to create new name for any type.

We might say that an Interface can be extended by declaring it more than one time; while types are closed.

https://itnext.io/interfaces-vs-types-in-typescript-cf5758211910